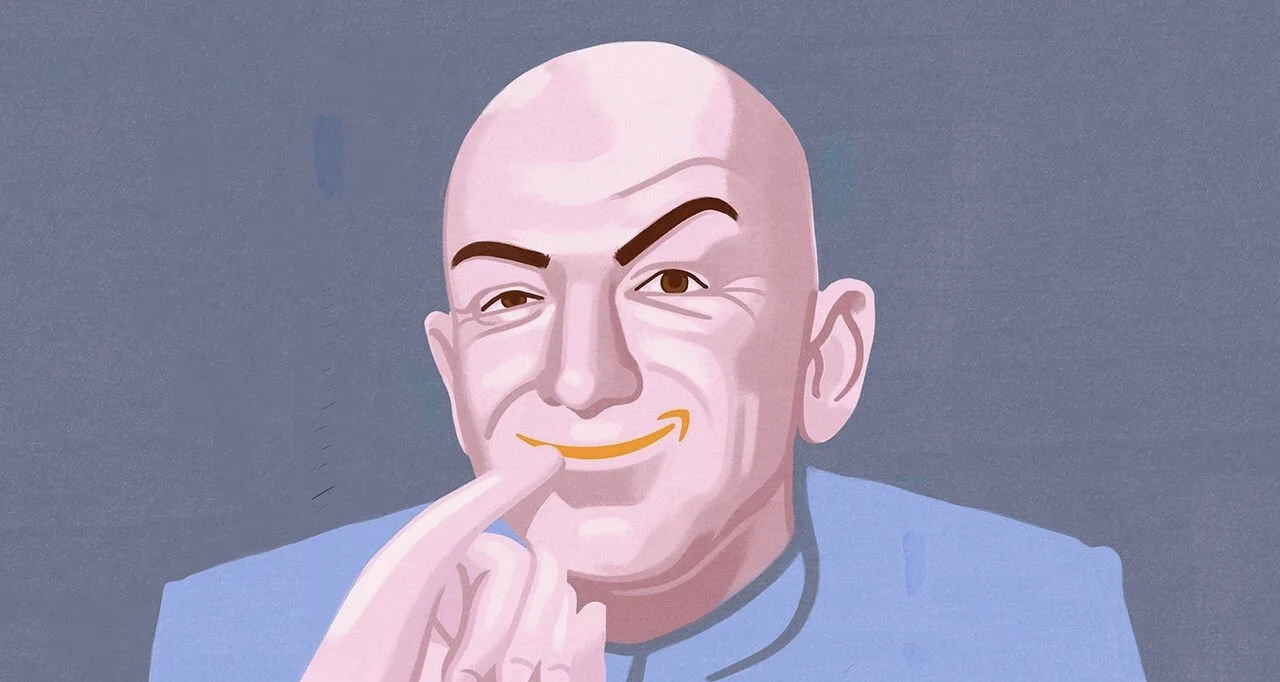

Amazon: Does it have too much control?

Flo Stephens | 16th March 2021

Amazon is the world’s largest online retailer, with its less well known web services provider, ‘Amazon Web Services’ known as one of the ‘big five’ companies in the U.S information and technology industry. For years it has provided consumers with the ease of clicking a button for the delivery of goods, now in “Prime Time” - all within one day. The company delivered 3.5 billion packages in 2019, one for every two human beings on earth. Every product you could need, from webservices to Fresh food delivery, Amazon provides.

As useful as this is, this retail giant has increasing control over the market and its suppliers. Despite not yet formally being recognised as a monopoly by the Federal Trade Commission, Amazon displays many of the characteristics that mean it should. A monopoly is defined as the power to control prices or to exclude competition, both of which Amazon has the power to do. With a 35% share of the US e-commerce market, Amazon is certainly a monopoly by British standards

But how did Amazon grow to the size it is today? To what extent can it influence the markets it operates in, and what does the future hold?

The main loophole that allowed Jeff Bezos, CEO, to grow Amazon was that it started at a time when conservative economists had undermined antitrust laws. These are laws that usually promote competition for the benefit of consumers. This meant that Bezos could use tactics that had once been illegal such as predatory pricing where he set the price of goods below the cost of production in order to drive out rival businesses, only to then raise the prices and buy out competitors, allowing Amazon to gain control over the market. This can easily be illustrated through Amazon’s competitor Diapers.com. Amazon spent thousands pricing Diapers.com out of the market and ended up buying them out cheaply. Now that Amazon has developed to the size it is today it has ‘monopoly leveraging’ allowing it to use the monopoly it already has over another market.

For example, Amazon has just opened its first grocery store in London, where consumers do not check out, but rather their purchases are tracked by highly sensitive sensors and cameras and they are then billed as they exit the store, on their Amazon account. Having already conquered many industries before, the recent introduction of Amazon Fresh and the new grocery store underline their ploy to take over the supermarket industry too.

But exactly how much power does Amazon have?

It was in 2017, when Amazon announced it was going to buy grocery store Whole Foods for $13.4 billion, that their true magnitude was put into perspective. Traditionally, after proposing a purchase like this the acquirer’s stock decreases. However, after only an hour of the announcement Amazon’s stock had risen by 3% which accounted to around $14 billion.

As a result, Amazon practically bought Whole Foods for free.

Being a monopoly is not illegal, however when a company demonstrates exclusionary conduct it is against the law, which many argue Amazon has, for example using ‘platform privilege’, authorities step in. Amazon preferences its own products and steers shoppers away from competitors. Hence when customers ask Alexa to “buy batteries” they will receive only one product: AmazonBasics batteries, privately owned by Amazon.

Will Amazon be facing a legal battle over this? Two decades ago, Microsoft lost a court case battle for bundling its own browser into its software. This made it more difficult for the competing browsers to be installed. The same could be said for Amazon’s default Alexa options – it is simple matter of democratic will that decides whether governments take them on. Just last month Australia proposed that Facebook pay news companies for showing them on their app, only to have Facebook news completely removed from the country. There is a growing consensus that the tech monopolies are simply too large to take on.

The book industry was the first of many to be dominated by Amazon. Today, Amazon controls 75% of the online sales of physical books as well as 65% of e-book sales. In 2016, economist Paul Krugman reported in the New York Times that “Amazon had as large of a market share in the book business as Standard Oil did in 1911, right before it was broken up into 34 different companies.” Many issues now exist within the book industry due to the monopoly power that Amazon holds. Publishers feel obliged to sell through Amazon as otherwise they would be missing out on one of the largest markets. However, this means that they have to face their bullying tactics. For example, previously when Amazon delayed the release of many orders of books from Hachette’s imprints until the company gave them the terms they wanted.

Not only is it harmful for suppliers, but also for consumers. I am sure you would have all viewed a product on the Amazon website, only to view it again the next day and for the price to have increased. Amazon raises prices once consumers are hooked through data that tracks buying habits.

Unfortunately, the service of Amazon Prime only makes their monopoly power stronger, and the demand is ever increasing. Today, Amazon ties over 150 million accounts down to the £8 a month. You do the maths. Any suppliers not providing this service are therefore disadvantaged as consumers cannot bear the extra wait of a few days. In order to be more successful, these sellers feel obliged to offer prime services just to keep a viable business, yet they lack the infrastructure and economies of scale to compete. This is limiting the opportunity of competitors if they do not partake within the service, an example of exclusionary conduct.

So what is the future of the online market place?

The arguments that this large company and others such as Facebook and Google should be broken up are strong - they are already facing scrutiny from government agencies. Breaking them up would increase competition as brands would no longer compete against the company owning the platform.

But is it fair to break down a company that has grown just by providing a useful service?

This method has already been trialed in India as it tried to regulate large corporations from running platforms whilst being retailers. Despite these regulations, Amazon found a way to avoid them and continued to grow.

There is also a growing argument that this is simply the future. There are two places where Amazon has failed, rather ironically, the Amazon Rainforest itself, where department store Bemol reigns supreme, and China. Alibaba, the tech conglomerate that does everything from social media to groceries, had already saturated the Chinese market. Like it or not, the global economy is being hoovered up by a small number of players with the pre-existing monopoly needed to invest elsewhere.

Whether or not Amazon is broken up, it is clear that some non-discrimination rules are required to offer a level playing field to all sellers and brands and to allow them to thrive. In the meantime, Amazon will continue to dominate. Just like the word ‘globalisation’ sprung from intellectual backrooms to business meetings worldwide in the early 21st century, there is a new term on the horizon. Democracy has become ‘Corpocracy’, raising even greater questions about who moves the pawns that govern contemporary politics. We are certainly hooked on Amazon, and it looks like politics is too. Who will win the game of international chess still hangs in the air, but Amazon certainly have the upper hand.